Written by Rodney Sharman

Hand

Murray Adaskin’s handwriting is engraved on the glass windows to Vancouver’s Davie Street, the only ornament in the concert space bearing his name. Murray was of the generation where left-handed children were forced to write with their right hands. Watching him write words or music was like watching someone draw: deliberate, slow, geometric. He took great pride in a beautiful manuscript. From him I learned to use ruling pens, osmiroid fountain pens, rulers and drafting desk. Murray was proud, too, that his manuscript is the first page of John Cage’s Notations, published in 1969, a book of great and unusual musical hands of the Twentieth Century.

Studio

My lessons with Murray Adaskin were in his home in the Uplands, Victoria. The main floor was a split-level, white and brick interior walls covered with works of art. Big portraits of Murray and Frances James Adaskin by Paraskeva Clark were hung over the white-carpeted stairwell. Descend, turn right, and you were in the large, cool room that served as Murray and Frances’ studio. It was a big, low-ceilinged open space where they held student recitals and house concerts. Murray taught violin and composed there; Frances taught singing lessons. Studio walls were covered in signed black-and-white photo portraits of the century’s greatest musicians, along with a few framed postcards and letters from Igor Stravinsky and Darius Milhaud. Murray and Frances knew them all.

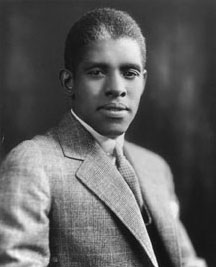

Sometimes in lessons, Murray would talk about the artist in the photo. I heard stories of Sir Ernest Macmillan, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Benjamin Britten, Yehudi Menuhin… Among the photos was Roland Hayes.

Roland Hayes

Roland Hayes was an African-American lyric tenor, the first artist to break the classical recording industry’s race barrier in 1939, and one of the greats. (Hayes was ten years older than Marian Anderson.) When Hayes performed in Toronto in the 1930s, he was refused a room in the Royal York Hotel because of race. The concert agents had booked (and paid for) Hayes’ room. Hotel employees, of course, had no idea what Hayes looked like before he arrived from the train station across the street. Murray was the violinist in the Royal York Trio, at the hotel when Hayes arrived. Murray went to the hotel manager, telling him he would resign if Hayes were not immediately given a good room. The manager fulfilled Murray’s request. Remember, this was the height of the Depression, violin jobs were scarce, and the Toronto Symphony very much a part-time orchestra. As Murray used to say: “If you want to play like an angel, be an angel! It’s that simple.” (In 1944 Frances James Adaskin studied voice with Hayes in Boston.)

Roland Hayes was an African-American lyric tenor, the first artist to break the classical recording industry’s race barrier in 1939, and one of the greats. (Hayes was ten years older than Marian Anderson.) When Hayes performed in Toronto in the 1930s, he was refused a room in the Royal York Hotel because of race. The concert agents had booked (and paid for) Hayes’ room. Hotel employees, of course, had no idea what Hayes looked like before he arrived from the train station across the street. Murray was the violinist in the Royal York Trio, at the hotel when Hayes arrived. Murray went to the hotel manager, telling him he would resign if Hayes were not immediately given a good room. The manager fulfilled Murray’s request. Remember, this was the height of the Depression, violin jobs were scarce, and the Toronto Symphony very much a part-time orchestra. As Murray used to say: “If you want to play like an angel, be an angel! It’s that simple.” (In 1944 Frances James Adaskin studied voice with Hayes in Boston.)

Violin

I don’t know how Murray came to own a Stradivarius, but I know (and knew!) I was very, very fortunate to hear my teenage string parts played, fingered, and bowed by Murray on this beautiful instrument. I watched his fingers, memorized their movements and drank in the magical sound. He eventually sold it, saying the violin needed to be played and heard more frequently. He taught me natural harmonics with all their individual qualities, and stressed the difference between each string. Murray had the most beautiful pizzicato I’ve ever heard. He would lightly stroke the string with his finger and pluck on the octave node, stressing that this allows the sound to bloom. The sheer beauty of sound and the opportunity to closely observe its creation nurtured the budding sound-sensualist within me.

Murray was likely the highest paid musician in Canada in the late 1920s, concertmaster of the biggest silent movie orchestra in Toronto. He was a beautiful violinist. His older brother Harry was his first violin teacher, oldest brother John played cello, younger brother Leslie played piano. Their father’s friends would ask why he would spend money on instruments and lessons for his sons, when he could send them law or medical school. He replied: “Because I want my children to have spiritual lives”.

Visual Art

In 1929, Murray travelled to Brussels to study with Eugène Ysaÿe, but Ysaÿe was in hospital recovering from a leg amputation. Murray found another teacher in Paris, Marcel Chailley. (Harry would study with him the following summers.) It was there Murray purchased two watercolours by Marc Chagall. These hung in Murray and Frances’ Victoria kitchen. The walls in the rest of the house were covered with art works big and small, even above the doorways. The living room dominated by a large and very good Jack Shadbolt. Most of the paintings were Canadian, including by Gordon Adaskin, a brother from his father’s second marriage. One of Murray’s few regrets was not purchasing a Tom Thompson in the 1930s. His art dealer called him to say he had something very special. Murray went to the bank for a $50 loan, when the bank manager learned it was for a painting, the manager scoffed and refused. Even in his 90’s Murray still cursed the bank manager as though it happened yesterday. The Painting is probably worth half a million dollars in 2019.

Words and Music

Murray was not a pianist, playing to maybe grade 4 RCM level. Still, he always played through my sketches at the piano at a slow, careful pace, often whistling the parts he couldn’t reach or that needed to be sustained. Milhaud assured him that not playing the piano meant that the hands would not fall into easy patterns or clichés. Murray was a natural orchestrator, and there are moments of magic in his music that look like nothing special on the page, but sound marvelous. One of my favourite moments is the appearance of the tuba in the slow movement of the viola concerto. It is as though a shadow falls across the orchestra. I know of nothing else like it in the repertoire. There is so much lyricism in his work, yet there is very little vocal music. Strange given that he was married to Canada’s leading new music soprano. Frances said she always asked for music, but when Murray finally wrote an opera in 1967, she was too old! Maybe the reason is that Murray came to composing relatively late in life, age 38. Maybe it was finding the right text. Maybe he thought it was better for their marriage.

Poetry and words were so important to Murray, who never finished highschool. Murray collected dictionaries and thesauruses. I remember his delight at the arrival of his enormous OED, complete with magnifying glass. Precision of language was so important, finding the right words. The last time I saw Murray was a few days before his death. I asked him how he was, and with great care he answered: “The candle burns out”.

Murray was a passionate music-lover. Some career musicians are not. He and Frances subscribed to the symphony, went to many student and faculty recitals. If the Adaskins were there, everyone performed a little better. This remained true after Frances died and Murray married Dorothea Larsen. Dorothea brought new energy to Murray’s musical life, new art, travel, recordings, suggestions for pieces, some especially written for the Lafayette Quartet, some for Dorothea’s grandchildren.

Mantras

In almost every lesson, Murray would tell me that the most important thing was to express one’s own voice as an artist. I studied with him from age 15 to 18, and these words became urgent later in life, when I was pressured to write another way. So many stories, so many parables and aphorisms have become part of me. I repeat them in my teaching, to my friends, to audiences. If I am a good teacher, it is because I learned from his fire and gentleness. It is years now, but I still miss him.

– Rodney Sharman, March 30, 2019, Victoria