CMC BC’s Legacy Composer Film Series celebrates the very first generation of composers to do something quite revolutionary – write Western concert music on the West Coast of Canada.

Made possible by a grant from the BC Arts Council, the films focus on five of these BC Legacy Composers: Murray Adaskin, Barbara Pentland, Rudolf Komorous, Jean Coulthard, and Elliot Weisgarber. Each of them contributed something unique, completely new and remarkable to the nation’s cultural mosaic, both through their body of work and the living legacy of students they inspired.

Scene from Murray Adaskin’s ‘A Wedding Toast‘

Produced and directed by Award-winning filmmaker John Bolton, the five short art films range in length from just over eight to fourteen minutes. Each film features a performance of a signature work by the composer, juxtaposed against a storyline unique to that piece of music, the performers, or the composer.

As we’ve celebrated these creative geniuses through film, we’ve been fascinated to discover the parallels between their lives and their work and the world of film and its impact on society.

The first documentary film in the series is called A Wedding Toast, based on Murray Adaskin’s arrangement of an existing song of that name, for Soprano and string quartet. He arranged it as a gift for the wedding of Pamela Highbaugh, a cellist and co-founder of the Lafayette String Quartet, and violist Yariv Alone. Their wedding took place 22 years ago at Goward House in Victoria, and John Bolton’s documentary intersperses original footage from their wedding with scenes of the couple revisiting Goward House and reminiscing both about the ceremony and about Murray Adaskin.

It’s interesting to note that Adaskin, whose neo-classical sensibility helped establish a distinctly new kind of Canadian sound, began his professional career playing violin for silent films in Toronto movie houses.

The film about Barbara Pentland is called The Lake, based on her Okanagan-based opera of the same name. It was filmed on location at Quail’s Gate Winery, featuring the historic log-cabin, ‘Allison House’, oldest home site in West Kelowna, built in 1873. The juxtaposition of Pentland’s modern atonal music and that early history surrounding first contacts between setters and First Nations is powerful.

Pentland was a cutting-edge member of Canada’s avant-garde, co-opting Webern’s serialism to create her own unique language. She wrote music for a film called The Living Gallery, and later, in 1968, wrote a piece called Cinéscene for chamber orchestra, which she described as:

Changing ‘frames’ of sound as in a contemporary film; characters move in and out of scene; there are distant views and close-ups, quick changes of densities. The tone rows are somewhat chameleon-like as are the characters.

The film about Elliot Weisgarber is based on a piece for flute and piano called Aki-No-Hinode, which translates as ‘Autumn sunrise’. It relates the story of Weisgarber’s daughter, flutist Karen Smithson, discovering that completely unknown work in the garage after Elliot’s death. It now resides in the very high-tech, robotic UBC Archives, and the film focuses on Karen’s visit to the archive to look at the original manuscript. Again, the juxtaposition between the ultra-modern, in this case the robotic archive, and the more ancient, traditional Japanese aesthetic of the piece, creates a fascinating contrast.

Weisgarber was an extraordinary innovator, the very first composer to incorporate Japanese and other Asian influences and instruments into western concert music – an innovative approach he termed ‘trans-cultural’. He wrote a number of scores for film and television.

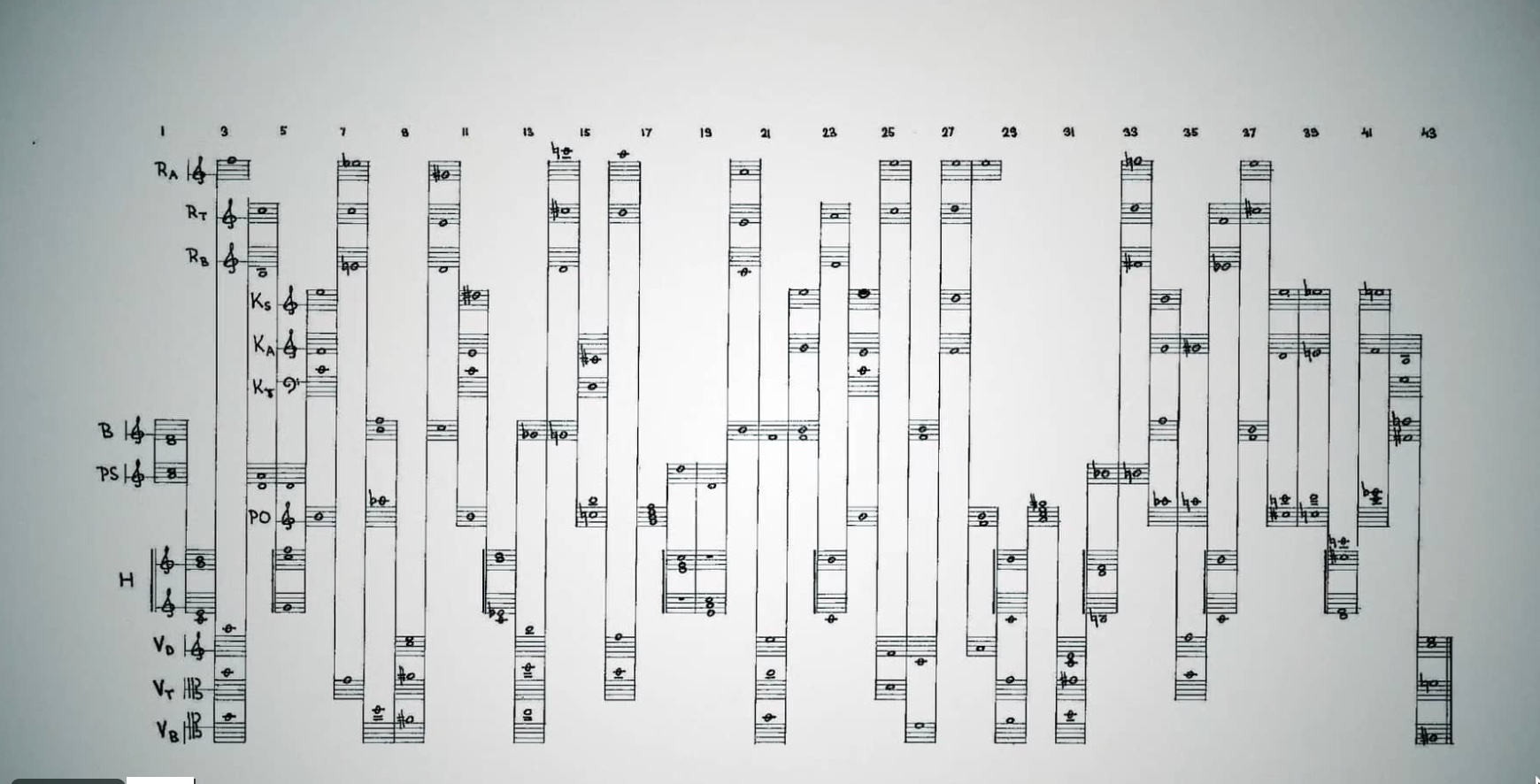

In the early 1970s, a musicologist from the University of Manitoba moved to the University of Victoria, and brought a group of early instruments with her. She asked Rudolf Komorous, then-acting Chair of the School of Music, if he would write a contemporary work for them. He took on the challenge, writing 13 Preludes for 13 Early Instruments, with each prelude one minute long and written using a different type of representational notation.

John Bolton’s Film 13 Thoughts About 13 Preludes for 13 Early Instruments animates the notation of the music, interspersed with interviews of Komorous at the newly-dedicated Rudolf Komorous Library of the Canadian Music Centre in Victoria, and with Christopher Butterfield, who was once his student and is now himself Director of the UVic School of Music. Yet again, it’s the juxtaposition of the ancient, in this case the instruments, and the modern language of the composition, that creates compelling interest.

Komorous was a founding member of the Czech avant-garde movement and his interest in Dadaism and Surrealism parallels that of the great French filmmakers of the 1950s and 1960’s. His ground-breaking music has inspired several generations of leading Canadian composers.

In his film about Jean Coulthard, The Pines of Emily Carr, Bolton visits the new Audain Art Museum in Whistler, BC, which features the largest installation of Carr paintings in the world. Coulthard visited Emily Carr in 1938 and inspired by her paintings, wrote The Pines of Emily Carr thirty years later. Filmed entirely on location at the Audain Gallery, the film follows soprano Cathy Fern-Lewis as she looks at the paintings and recites text written by Emily Carr. In this case it is the unity of music and subject that is so powerful.

Coulthard’s eponymous embrace of the western Canadian landscape produced both a lyric and landmark body of work rooted in its place and time. She wrote her first composition – Cradle Song – in 1927, the same year Al Jolson’s The Jazz Singer was released – the very first feature-length film ever produced with sound.

I find that link to be more than coincidental. It provides a lens to help us place the music of that generation of composers in a distinct historical, social, and cultural context. And it helps us understand how modern — how revolutionary, in fact — their music was juxtaposed against the times they were living through.

As you watch this clip from The Jazz Singer, it’s impossible not to think how old-fashioned it is – Jolson’s ‘silent film’ eyes, the Vaudevillian gestures, the dance steps, the costumes …

Scene from Jean Coulthard’s ‘The Pines of Emily Carr‘

And yet that generation was one of the most modern, the most innovative in history. They invented the world we live in. They were the adventurers. They did everything we take for granted first. We’re in fact the old-fashioned ones, plodding along in the well-worn tracks they laid down nearly a century ago.

The Roaring 20s was a time of dramatic social and political change. More North Americans lived in cities than farms for the first time in history. Women had only recently gained the right to vote. That generation was the first to produce and listen to both radio and television. The first generation to drive cars. The first to fly.

They created mass communication, giving rise to the mass culture and mass consumerism we are part of today. The first commercial radio station hit the airwaves in 1920; three years later there were more than 500, and by the end of the 1920s, there were radios in more than 12 million households. Everyone, everywhere listened to the same music – jazz – and did the same dances.

The year The Jazz Singer was released, people bought 100,000,000 records. 75% of the population were going to a new movie every week and nearly one in five people owned a car. By the end of the decade, the Roaring Twenties had crashed into the Great Depression, traumatizing an entire generation.

But what they created lived on. As does the body of work created by that remarkable generation of composers to write the first western concert music from BC.

Our thanks to John Bolton and Maggie MacPherson for creating these delightful art films; and to the BC Arts Council for the grants that made the films possible.